Are We Ready For Next Pandemic?

This article will appear in the forthcoming Spring 2025 issue of Johns Hopkins Magazine

From afar, the images look like clusters of tiny, multicolored dots strewn across paper. “But the dots tell a story,” immunologist Gigi Gronvall says about the two prints she framed and hung behind her desk at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

One image shows the meticulous mapping of a London-based cholera outbreak in 1854 by British physician John Snow, whose work pinpointed the source of the sickness: a contaminated water pump in the Soho district. “The prevailing theory at the time was that cholera spread through air,” Gronvall says of Snow’s groundbreaking work. “But by gathering and mapping the data, Snow uncovered what we know to be true today—cholera spreads through contact with sewage and feces.”

Dots delineate a different infectious disease in the other, more complex image. There, arrows point up and down and sideways to pink, black, and blue circles, squares, and triangles, tracking viral and genetic material gathered in January 2020 from animals and stalls at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China. A data visualization from a paper in the journal Cell (September 2024), the intricate markings reveal the presence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in the materials tested.

For Gronvall, a national security expert and senior scholar at the Center for Health Security, every study like this contributes to our body of scientific knowledge and reminds us, in this case, of a pandemic that led to the loss of more than seven million people worldwide and trillions of dollars from the U.S. economy. People associate pandemics with the risks posed to human health, but they affect all aspects of society, she says. “That’s another reason we need to figure out how COVID started and what we can learn from it.”

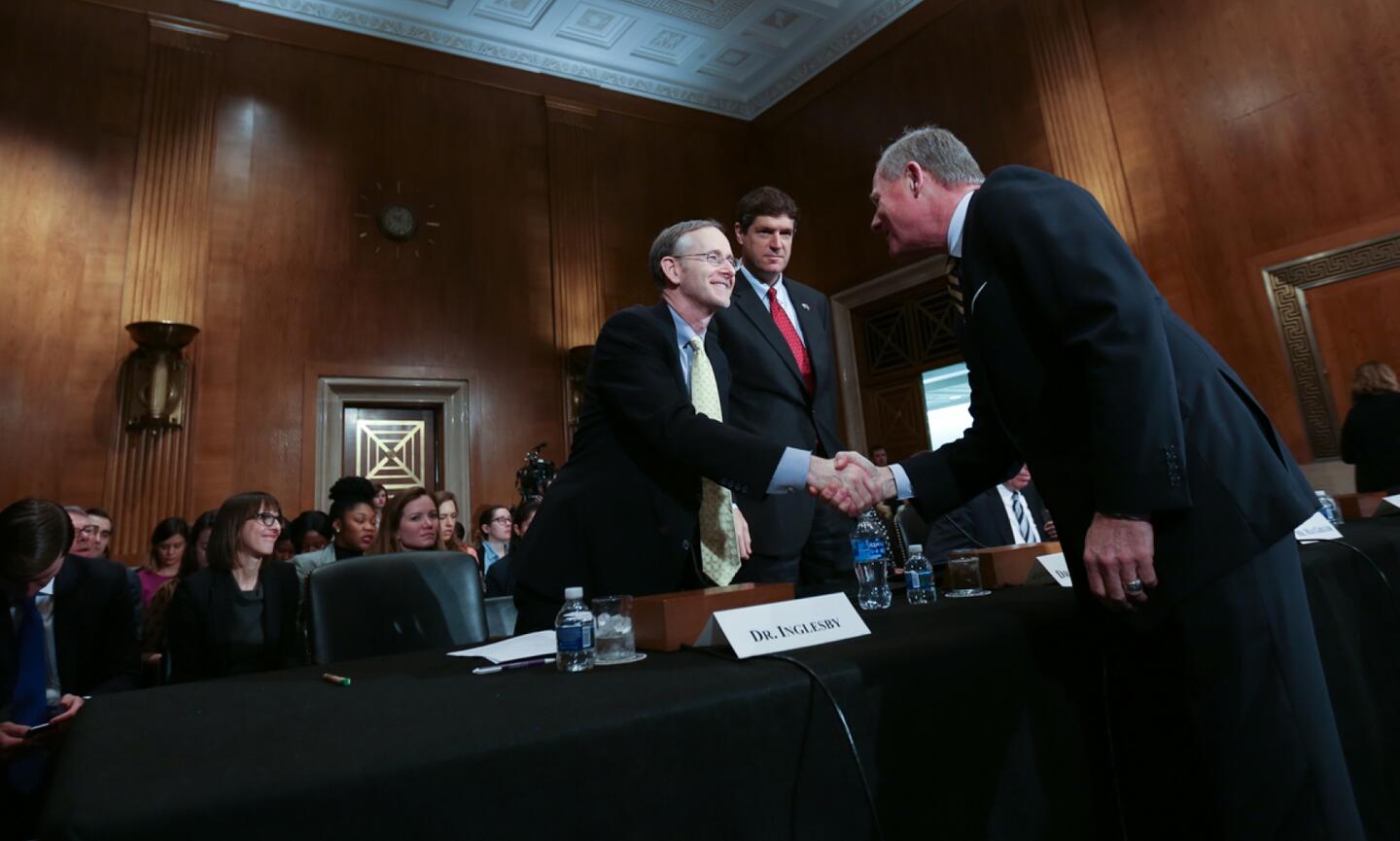

Although the scientific community lacks consensus on whether COVID-19 originated in the Wuhan market or elsewhere, most scientists agree on another matter: We can expect more pandemics to come, owing to factors like climate change, mass migration, globalization, and human encroachment on wildlife and insect ecosystems. According to the center’s director Tom Inglesby, who served in COVID-related advisory roles during the pandemic at the White House and in the Department of Health and Human Services, “as temperatures change, people are moving around the world more rapidly than ever before … and intruding into ecosystems that used to be made up entirely of animals or insects.” This, in turn, creates opportunities for humans to get infected by new diseases and disease strains.

Another factor contributing to the likelihood of future pandemics are the concentrations of people living in megacities like Tokyo, Delhi, and Shanghai—to name three on a fast-growing list of cities with more than 10 million inhabitants. “In some, people live incredibly close together without great sanitation, creating conditions for rapid spread, Inglesby says.” This happened last year, for instance, in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s capital city Kinshasa, home to 17 million. There, a new, more contagious strain of a disease typically confined to rural areas, mpox, spread quickly. As a result, mpox now poses a threat not only to Kinshasa and the DRC but also the world, given the international flights going in and out of Kinshasa daily.

Over the past few decades, public health experts have watched infectious diseases spring up and evolve in surprising ways. That’s a main reason the Center for Health Security was created in the first place, Inglesby says of the group that started in 1998 and has helped fight anthrax attacks and other bioterrorist threats, plus outbreaks of swine flu (H1N1), yellow fever, the Ebola and Zika viruses, and COVID-19.

Chances are, Inglesby says, experts won’t be able to predict the next pandemic. It could be the bird flu ravaging U.S. cattle and poultry farms and infecting humans. It could be Zika or Dengue fever, spread by mosquitoes, or another strain of influenza or coronavirus. “No one really knows,” he says. “That’s why we need to heed lessons from the past and prepare.”

Today, five years after COVID-19 spread to every continent on Earth, killed millions, and left roughly 400 million people with brain fog, breathing difficulties, and other symptoms of long COVID, Inglesby and others want to share and highlight the lessons learned to better prepare us for the next one that will inevitably occur.

Much of what they learned relates to the months leading up to the pandemic, “a critical window of opportunity to do everything you can to contain the disease,” Inglesby says. It involves decisions made at the executive level to combat a fast-spreading new virus, along with the timeline and manner in which officials share information and deploy countermeasures. It also involves the steps taken—or not taken—to contend with misinformation, which Gronvall, who teaches a class on the 1918 influenza virus that killed roughly 50 million, says we can count on transpiring in all pandemics.

“We’ll be unpacking COVID for decades to come, with doctoral students and scholars poring over the data,” Gronvall says. But with other pandemics on the horizon and COVID-19 continuing to mutate and cause lasting complications for people with and without chronic health conditions, experts say our country can’t ignore what it learned and put its head in the sand.

On Jan. 1, 2020, epidemiologist Caitlin Rivers opened her inbox to find an email from the disease outbreak surveillance system ProMED, sent one minute before midnight on New Year’s Eve.

“I have a bad feeling about this,” the senior scholar at the Center for Health Security thought to herself, unintentionally channeling the famous Star Wars line.

The email reported a cluster of pneumonia-like cases of unknown cause in Wuhan, the sprawling capital city of central China’s Hubei province, with a population of 11 million. Government officials in China hadn’t yet reported the illnesses, but the low-tech email service ProMED had pieced together the news from active chatter on Weibo, a Chinese microblogging site.

Following ProMED’s alert, media outlets worldwide started reporting on the strange sickness that turned out to be the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. But according to a report by the nonprofit research institution Project Information Literature, other stories dominated the U.S. news cycle, such as the Senate’s impeachment trial of President Donald Trump and the tragic death of basketball star Kobe Bryant. “Buried deeper in the news flow were reports of a mysterious flu spreading through China,” the report reads. “To the Americans who followed this story, this threat seemed safely distant.”

But faculty at the Center for Health Security saw clear warning signs and took swift action. In a Foreign Affairs article published on January 31, 2020, Inglesby reminded the world of a tenet of public health: preparation is the key to an effective response, or, as Benjamin Franklin put it, “By failing to prepare, you prepare to fail.”

According to Inglesby, as evidence mounted in January that the novel virus could morph into a pandemic, “governments [worldwide] needed to act immediately by organizing for the worst-case-scenario and turning on all required systems”—a tall order that involves stockpiling diagnostic tests and protective equipment, readying hospitals and health care workers, preparing schools and teachers, and pooling resources and teams to develop a vaccine, therapeutic drugs like antivirals, and the manufacturing supply chain to produce and distribute these products in record time.

“If, for some miraculous reason, a pandemic didn’t occur, then the extra work would leave us better prepared for the next one,” Inglesby says.

Did the right people listen?

Some pockets of the federal government “were quietly, extremely concerned and doing what they could to prepare,” Inglesby says. But the government’s main effort involved regulating travel from China, with passengers facing health screenings and potential quarantines.

More travel restrictions and bans followed, measures that experts say did little to prevent the spread of a virus already widely circulating. According to Inglesby, “there should never have been an assumption that shutting down travel was a foolproof strategy. People were moving around the world all the time, and it was too late.”

In February 2020, as COVID cases multiplied, Inglesby attended a federal government meeting with health care system leaders. “People were worried, but the meeting was more like a brainstorming session, instead of [an action plan] to start implementing specific steps to prepare hospitals and health care workers,” he says.

Why no plan?

Pandemic preparedness had been a federal priority since 2005, when President George W. Bush devoted $7 billion to the cause. “A pandemic is a lot like a forest fire,” Bush told scientists at the National Institutes of Health. “If caught early it might be extinguished with limited damage. If allowed to smolder, undetected, it can grow to an inferno that can spread quickly beyond our ability to control it.”

The Obama administration continued the work, taking an aggressive approach to the Ebola epidemic in 2014 and establishing a global health security directorate (through the White House’s National Security Council), with a mission to prepare for and, if possible, prevent the next outbreak from turning into an epidemic or pandemic. The directorate [created a 69-page playbook, delineating how to guide government sectors through the complex work of fighting health threats.

In 2018, however, the Trump administration dismantled the directorate, claiming it was overstaffed and needed streamlining. Some staff members merged with other groups, while others left their positions, resulting in what the directorate’s former leader Beth Cameron described as a diminished federal workforce devoted to monitoring and mitigating disease spread when COVID broke out.

“In a health security crisis, speed is essential,” Cameron wrote in a March 13, 2020, op-ed for The Washington Post. “When this new coronavirus emerged, there was no clear White House-led structure to oversee our response, and we lost valuable time.”

For a country as large as the U.S., creating a unit to oversee and coordinate global health security, with backing from senior government officials, is essential, experts say.

Inglesby agrees. Fighting a disease, he explains, “involves tremendous coordination among not only government sectors but also private companies, nonprofits, and countries and organizations worldwide. It requires a structured, strategic approach.”

Sometimes it makes sense to withhold information or quell fear with words of reassurance. When a friend suffers a loss, one might say, You’ll get through it. Everything will be OK.

When it comes to a health threat, however, placating the public isn’t the right strategy, experts say, and it’s a lesson Inglesby and Rivers hope the country will take from the pandemic.

“The job of public health and political leaders should never be to overly reassure,” Inglesby says. “The job is to be factual and to provide maximum information to people and their families so they can make good judgements and lower their own risk of spread.”

But as Rivers explains in her recently released book, Crisis Averted: The Hidden Science of Fighting Outbreaks, senior officials downplayed the threat in the weeks before and after COVID became a pandemic. Alex Azar, the secretary of Health and Human Services at the time, announced at press briefings in late February that the risk to the American public remained low, while President Trump tweeted that the health threat had been “inflamed … far beyond what the facts would warrant.”

For Rivers and others monitoring the situation, “the risk to the United States was anything but low … [yet went] unnoticed by most of the public and [was] actively denied by elected leaders,” she says. That’s why, when the U.S. declared a national emergency on March 13, the country was largely caught off guard.

Rivers, in Crisis Averted, stresses the importance of sharing information in a straightforward, timely manner. “Clarity is a core tenet of public health messaging,” she writes. Delivering bad news is difficult, and even the best health officials sometimes use “opaque language” and “fuzzy jargon” to soften the blow. The problem with these approaches, however, is that they don’t “give the listener any sense of the magnitude of the problem, or any direction about how concerned to be,” she says.

Instead, people can more easily grasp information delivered in plain language with concrete examples, Rivers continues. This is a goal of public health messaging, but it mostly went unmet early in the pandemic.

As Inglesby explains it, “the more we’re in the mode of dismissing or downplaying the [situation] or of reassuring people, the more anxious they’re going to get,” and the more susceptible they’ll be to misinformation.

Instead, people need specific information and evidence-based advice about their own circumstances. “Some of us face higher risks than others, whether we’re elderly or have an underlying condition, or we have a grandmother living with us,” he continues. “Everyone needs practical guidance.”

“Science is slow,” says Gigi Gronvall, sitting at her desk one morning in front of the images that remind her of the knowledge and benefits a society can reap when scientific breakthroughs occur. “But science is far more effective than jumping to conclusions.”

During the pandemic, with schools and businesses closed and loved ones getting sick and dying, “no one wanted to wait for information or be told what they could and couldn’t do,” she says. “No one liked the disciplinarian,” and public health became an easy target.

According to a study by the Bloomberg School, 57% of leaders of local health departments surveyed nationwide became targets of harassment between March 2020 and January 2021, with droves of practitioners opting to leave their positions. “Constrained by poor infrastructure, politics, and the backlash of the public they aimed to protect, public health officials described grappling with personal and professional disillusionment, torn between what they felt they should do and their limited ability to pursue it,” the study reports. “For some, the conflict was untenable.”

Why did public health become the scapegoat of a nation on lockdown?

From Inglesby’s perspective, the backlash stemmed partly from an over-reliance on the CDC to make decisions beyond the scope of its expertise. “The CDC is full of talented scientists, but as a health research agency, it wasn’t set up to respond 24/7 to questions from the government and policymakers about matters of logistics and economic and societal tradeoffs, such as whether to close schools and businesses and cancel events,” he says. “These are political and civil-society decisions that require a collaborative effort, with people representing various interests weighing in to determine the best course of action.”

Founded in 1946 to stop the spread of malaria, the CDC serves as the nation’s leading public health agency, responsible for providing scientific guidance on the spread of infectious diseases. The Atlanta-based agency is staffed with epidemiologists, virologists, and other experts in disease control and prevention, not in areas like economic growth and K-12 education. When asked, in the summer of 2020, to provide guidance on the return to school for students and teachers, the CDC submitted a report to the Trump administration indicating that the move would pose risks to a country experiencing 40,000 to 100,000 new cases of COVID every day—and to a nation with an already-overwhelmed health system.

The administration pushed back on the report, and many blamed the CDC for keeping kids out of school. According to Inglesby, however, the CDC was simply doing what it was set up to do: offering guidance on the matter, as it relates to curtailing harm done by the virus. “It became all too easy to blame [the agency] for a decision that needed experts in additional areas to weigh in,” he says.

The backlash on public health also stemmed from the learning curve involved in combatting a wily new virus behaving in unpredictable ways, experts say. “We didn’t have all of the answers, and new scientific evidence was emerging all the time,” Inglesby explains. “A study would be completed or half-completed. A new variant would be identified, and the message to the public would change.”

One example: face masks.

Early in the pandemic, scarce information existed on whether masks could stave off COVID-19, so officials didn’t suggest wearing them. That changed, however, as data revealed that masks slow down the disease transmission, leading the CDC to alter its guidance. “Some political leaders and members of the public accused the CDC of reversing positions and [lacking competence],” Inglesby says, referring to the allegations of “flip-flopping” that resounded nationwide. “What was missing from the conversation, however, is that changes are inevitable in an agency devoted to scientific research—that’s the nature of what researchers do.” They gather evidence and conduct studies, shifting recommendations as they narrow in on the truth.

How public health officials present information makes a difference, experts suggest. “The public doesn’t want to hear heavily scientific explanations, just as they don’t want to be told everything will be OK, without any specifics,” Inglesby says.

Gronvall recommends an approach comparable to a police chief speaking at a press briefing. “The key is to strike a cadence that reinforces a message along the lines of, ‘This is what we know right now, and it’s why we recommend X precaution. When we learn more and if the guidance changes, we’ll update you right away.'”

This way, the message comes across not as a command from all-knowing experts but as an open sharing of evidence-based information for people to use—or not use—to make decisions. The choice stays with the individual, who becomes an informed partner in protecting their health and that of their loved ones.

Tara Sell, a senior scholar at the Center for Health Security, specializes in misinformation—and its ability to turn people away from life-saving health advice. During the pandemic, she mined social media and networking forums for misleading posts about everything from face masks and social distancing to vaccines and anti-viral treatments.

“Misinformation eroded millions of people’s trust in public health,” Sell says. “It will take a lot of work to rebuild it.”

From her research, she discovered that misinformation stemmed in part from partisan politics. “Whether to wear a mask, whether to get a vaccine—those choices became tied to people’s political identity, which wasn’t good for the public and brought consequences that continue today,” Sell says. Since the pandemic, for example, at least 30 states have passed laws to limit public health authority, and health officials in many of those states can no longer issue mask mandates or close schools.

For Gronvall, partisan media outlets fueled misinformation by giving airtime to anchors who contradicted health guidance and sowed doubt among viewers. On “Tucker Carlson Tonight,” for instance, Carlson spoke out repeatedly against vaccines, going so far as to compare President Biden’s vaccination plan to the lethal and torturous medical procedures imposed by the Nazis during the Holocaust. In 2021, he referred to the vaccine as “the greatest scandal in my lifetime, by far,” and openly discouraged his roughly 3 million viewers from getting vaccinated.

The media’s influence on health compliance during the pandemic hasn’t been thoroughly studied, Gronvall says, and she worries the breeding ground for misinformation still plagues us. “As a society, we haven’t addressed the financial forces that went into dismantling public health messages and dissuading people from protecting their own interests,” she says.

Sell agrees, adding: “Misinformation is a predictable part of health emergencies, so much so that we’ll know what to look for the next time around.”

From her research, Sell noticed striking similarities among misinformation spread during COVID and other crises. For example, tales of infertility nearly always crops up, with reports of, say, a vaccine preventing women from conceiving or delivering a healthy baby. False claims abound about health treatments that use children as guinea pigs, along with conspiracy theories about a government’s ill intentions or a pharmaceutical or tech company’s financial greed.

Society’s most susceptible members often fall prey to the messages. “Pregnancy and early motherhood, for instance, are vulnerable times for women,” Sell says. “You’ve got a lot of things you don’t know, and so you search the internet for information and find a lively audience talking about things that speak to your situation. You get hooked.”

To share what she learned, Sell and her colleagues worked with the CDC to produce a playbook for directors of local health departments to use to identify and address misinformation. The playbook includes instruction on things like how to address rumors, frame messages, and connect with communities to build trust and partnerships.

“As health scholars, we tend to look at situations through the lens of case numbers and infection rates, but other people’s values also matter,” she says. “We need to step out of our bubbles. We need to listen with empathy.”

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, as the deadly disease ravaged one battalion after another on the battlefields of World War I, governments went to great lengths to hide the circumstances, fearing the news would lower morale and lead enemy forces to take advantage of the depleted troops.

In the U.S., President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the Espionage Act of 1917, preventing anyone from documenting or discussing anything that would disadvantage the country’s military position. The following year, Wilson passed the Sedition Act, a more stringent measure that made it illegal—and punishable by a 20-year imprisonment—for anyone to write, publish, or utter a word that might hinder the U.S. war effort. This, of course, meant keeping quiet about the strange illness killing millions on U.S. soil and across the Atlantic.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Wilson’s suppression of free speech fostered a breeding ground for misinformation about a virus that became known, incorrectly, as the “Spanish flu.” A neutral country in World War I, Spain was among the only countries reporting deaths and illnesses caused by the virus. Word spread that the virus originated there.

Studies reveal that “the ‘Spanish flu’ most likely started at a military camp in Kansas,” says Gronvall, who teaches a class on the 1918 pandemic at the Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Gronvall says her students chime in regularly with stories about COVID—and similarities between the pandemic they experienced firsthand and the one they’re learning about in class. She talks to students about rising threats like H5N1, a matter that weighs heavily on those at the Center for Health Security.

At the time of this writing, H5N1, a strain of influenza spread by wild birds and highly contagious and lethal in poultry, continues to wreak havoc on the U.S. poultry and cattle industries, having infected commercial and backyard poultry flocks in all 50 states and cattle herds in at least 16, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the CDC. Seventy humans have tested positive, including veterinarians [and others] with no known contact with infected cows or birds, “which suggests we’re missing cases,” Gronvall says. Mammals are also contracting the disease, with H5N1 showing up in red foxes, racoons, bobcats, and, even, domestic cats, among other animals.

“I’m chronically worried,” Inglesby says about H5N1. “There’s no evidence right now that it can spread from human to human, but that could change in ways that allow it to transmit efficiently between people.”

If that happens, the outcome could be disastrous. “The lethality of H5N1 infection in a new epidemic would depend on the exact strain, but in the past, there was very high lethality in humans infected with this virus,” Inglesby explains.

Experts say that the U.S. needs to prepare not only for H5N1 but also for the slew of other infectious diseases with epidemic or pandemic potential. “We live in an age of pandemics and have to count on an increase in infectious disease outbreaks,” Inglesby says. “We have to create [the infrastructure] to develop medicines and vaccines rapidly and surveillance systems that can make quick diagnoses.”

No such pandemic response system exists right now, and it can’t happen by the hands of a single country—it requires a global effort, Inglesby indicates.

Since the bird flu broke out in the U.S. in 2022, world experts have been watching what many considered a lackluster response by the Biden administration to contain the disease. Diagnostic testing for H5N1 is in short supply, and in many states, testing cattle isn’t mandatory. Infected but asymptomatic cattle can go unnoticed, and farmers who fear economic or other repercussions (roughly half of U.S. farmworkers are undocumented immigrants) may be reluctant to report sick cattle and unable to seek medical care if they fall ill themselves, owing to a lack of health insurance.

“The country needs to remove barriers that get in the way of farmers reporting illness or seeking help,” Inglesby says. In 2024, “the USDA implemented a financial incentive for farmers who report illnesses. That’s a step in the right direction.”

Still, the number of cattle and humans with H5N1 probably far surpasses the number of cases reported, Inglesby suspects. And the coordination it will take to combat a virus that affects both humans and animals is “much more complicated than fighting COVID because of the collaboration it takes between the USDA and CDC,” he says.

A vaccine for the strain of H5N1 running rampant across the U.S. doesn’t yet exist, though pharmaceutical companies such as Moderna and Pfizer are working on it. Roughly five million doses of an older vaccine that targets other bird flu strains exist, but those haven’t been made available to farmers, who face the most risk.

“Did we learn nothing from COVID?” Gronvall wonders.

Right now, efforts are underway to restructure, shrink, and limit the powers of the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the CDC, and practically all government agencies, with budget freezes halting medical research and public health initiatives. “This is incredibly worrisome for several reasons,” Inglesby says, “including what it’s doing to public health budgets at the state level, which rely on money from the CDC.”

Gronvall says the abrupt slashes to research and public health budgets, combined with cuts to services that advance and protect human health, are arriving as our country and world face an unprecedented health threat, with more to come.

“We don’t know enough about H5N1 or other viruses with epidemic or pandemic potential, and we need to learn,” she says, gesturing to the pair of images on the wall behind her, the two emblems of acumen gained through data collected and analyzed. “The only way to learn is by doing more research.”

Emily Gaines Buchler is a senior writer at Johns Hopkins University.

George W. Bush

https://hub.jhu.edu/2025/03/19/lessons-learned-from-covid/