Kant’s Insights on Freedom Amid Climate, Trade Strife

A decade ago, the majority of nations committed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals , pledging to “leave no one behind” by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions globally by 2050 .

Ten years on, the sentiment regarding such aspirations is skeptical and the mood gloomy. With the rise of autocracies and the influence of libertarian tech-billionaires on politics , goals such as development for all and climate neutrality seem to be relics of the past.

The United States, the most powerful country in the world, is at the heart of this shift. In 1776, the U.S. declared independence and was founded on the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness . Today, however, it is increasingly known for its disregard of life , legislative attacks on civil liberties and creating global insecurity through tariffs .

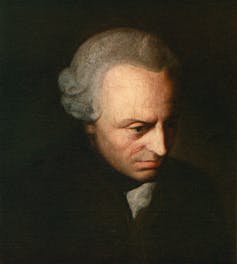

In the midst of all this, it’s important to remember ours is not the first generation to face dark times. As my recent research argues , Immanuel Kant’s philosophy can offer us valuable tools for navigating today’s challenges.

In 1776, the same year the U.S. was founded, Kant was preparing his breakthrough critical philosophy and lecturing on freedom and pragmatic anthropology, all while living in the absolutist monarchy of Prussia .

At the time, Prussia was using its military to expand its territory and enforce internal colonization over land and peoples .

Amid this, Kant observed the contradictions of human nature – people who acted both good and bad, cruel and respectful of others – and described humanity as “crooked timber.” Yet Kant insisted on viewing this “crooked timber” through the lens of freedom.

At the centre of Kant’s universalist, freedom-focused vision for the future was the idea of a world where all people lived in dignity. It is focused on autonomy as the capacity to self-legislate. Freedom served as his North Star for what is today called “backcasting,” or thinking backward from a desired future to identify possible paths toward achieving it.

In this spirit, Kant observed the rise of competitive markets that rewarded selfishness and greed, and argued that law and international co-operation – what he called a federation of republics – could turn antagonism into springs of progress. In other words, he analyzed the discord and conflict of his present for signs of possible progress.

Crucial for the identification of such possibilities was the freedom of public reason: people thinking for themselves and contributing to public debate.

What can we learn from Kant about navigating today’s multiple crises?

First, focus on freedom from a long-term perspective. The current trade war will likely reduce economic growth, but they may also advance the re-regionalization of economies – an idea long supported by post-growth economists seeking sustainable prosperity .

However, regional production is not inherently good. Rather, we need a public discussion about which essential goods – food, for example – are best mostly supplied regionally, by whom and where international co-operation is called for.

Second, Kant’s insights remind us that freedom must be pursued within the reality of a shared, finite planet. Climate change is not a problem that can be solved overnight. Emissions don’t care about the threats and angry fits of autocrats . It’s a global, complex challenge that requires long-term planning processes.

There are signs of progress in this regard: in 2024, the United Kingdom reported greenhouse gas emissions to be at their lowest levels since 1872 thanks to long-term planning. Canada, after opting out of the Kyoto Protocol in 2011, finally saw emissions start to fall in 2025 following a renewed commitment to international climate goals and planning.

But this progress is fragile. The chaos of Trump’s tariff wars must not lead our politicians and policymakers to prioritize short-term economic and political gains over long-term climate strategies.

Prime Minister Mark Carney and Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre’s support for pipelines , for instance, is at odds with evidence that fossil fuel expansion will lock in emissions .

It also diverts public money away from cheaper sources of renewable energy and supporting citizens through a just energy transition . With trade wars and economic insecurity, inflation will likely increase costs of living. This will hit poorer households harder, making this a matter of both environmental and social justice.

Third, for Kant, current lifestyle expectations are no guide for the core of future freedom. So if the American treasury secretary asserts that ” cheap goods are not part of the American dream ,” can we, paradoxically, detect an unexpected sign of possible progress?

The answer is yes – if we take that example as evidence that worthwhile aspirations cannot be captured by consumerism but call for a more sustained effort.

While modern consumers are willing to make big efforts – such as for daily gym and running routines – can similar energy be released to collective dreams of progress and saving the planet? For Kant, future freedom requires seeing beyond individual to collective aspirations. This relies on shared goals that can be articulated through foresight and supported by a vibrant, critical public sphere.

In Kant’s time, the public sphere mainly consisted of the Republic of Letters , a network made of intellectuals and writers in the late 17th and 18th centuries engaging in open debate.

Today, by contrast, much of our communication takes place on social media platforms that prioritize short-form formats, reward anger over analysis and are owned by a few global corporations structured to maximize profits rather than the quality of public deliberation. To counter this trend, regionally diverse, independent news providers are needed along with decentralized, open source social media.

But above all, in an era of climate crisis, political polarization and economic instability, Kant reminds us of what he called a “Denkungsart:” an “art of thinking” or mindset based on freedom and possibility in a long-term perspective.

Rafael Ziegler does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View Original | AusPol.co Disclaimer