Low-Dose Weight Loss Drug Eases Heart Failure Signs

Research Highlights:

BALTIMORE, July 23, 2025 — Low doses of the injectable weight-loss medication semaglutide may improve symptoms of a hard-to-treat type of heart failure. This effect happened through direct action on the heart muscle and blood vessels, despite resulting in no significant weight loss, according to preliminary research presented at the American Heart Association’s Basic Cardiovascular Sciences Scientific Sessions 2025. The meeting, held in Baltimore, July 23–26, 2025, offers the latest research on innovations and discovery in cardiovascular science.

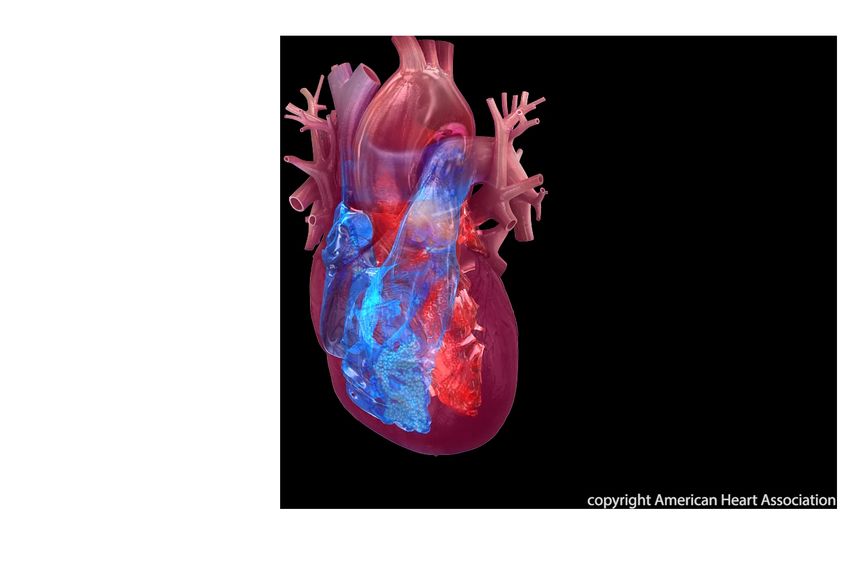

Heart failure occurs when the heart is unable to pump enough oxygen-rich blood to meet the body’s needs, resulting in shortness of breath, fatigue and other symptoms. One type of left-sided heart failure, called diastolic failure, occurs when the left ventricle can’t relax normally because the muscle has stiffened. As a result, the heart can’t fill with blood as it should during the time in between each heartbeat. This is known as heart failure with preserved ejection, or HFpEF.

“HFpEF is a major and growing health concern, accounting for about half of all heart failure cases. It’s becoming more common as our population ages and as more people are diagnosed with conditions like high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes and obesity,” said study author Mahmoud Elbatreek, Ph.D., a postdoctoral scientist in the department of cardiac surgery at the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Many people with HFpEF also have obesity. Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (government agency that regulates food, drugs, tobacco and other public health issues) has not approved semaglutide for the treatment of HFpEF. In a clinical trial published in 2023, the STEP-HFpEF trial, weekly injections of a standard dose of semaglutide significantly reduced symptoms in people with obesity and HFpEF, boosted their exercise capacity and improved their quality of life. “However, one big question remained: Is semaglutide’s main benefit simply due to weight loss, or does it also have a direct, positive effect on the heart and blood vessels?” Elbatreek said.

In the new study, Elbatreek and colleagues used two animal models that closely mimic humans with HFpEF. Rats genetically prone to obesity, and pigs were treated to induce high blood pressure and fed a salty, fatty diet. To observe the direct effect of semaglutide on the heart and blood vessels independent of its well-known weight loss effect, the animals were separated into two groups: one group received weekly injections of a low dose of semaglutide and the second group, the control group, received a placebo injection.

The study found that, despite resulting in no significant weight loss, the low-dose semaglutide treatment resulted in:

“The real surprise, and frankly, the most exciting discovery for us, was how many direct, positive effects semaglutide had on heart and blood vessel function despite resulting in no significant weight loss,” Elbatreek said.

“Our findings may provide a new treatment option for more people with HFpEF, including those who are not obese or who cannot take higher doses of semaglutide. This is hopeful because using a lower dose of the medication would likely lead to fewer side effects, like those sometimes experienced in the stomach or gut, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain,” Elbatreek said.

The American Heart Association’s Acute Cardiac Care and General Cardiology Science Committee member Amanda Vest, M.B.B.S., M.P.H., FAHA, said, “This animal study is interesting because the results differ slightly from the pattern we saw in the human obesity-heart failure study and align more with the results from a cardiovascular risk-reduction study. In the clinical trial of patients with obesity and HFpEF called STEP-HFpEF, greater percent weight loss with semaglutide was linked to greater symptom and functional capacity improvements. Conversely, in a cardiovascular outcomes study of participants with overweight or obesity and no diabetes (neither Type 1 nor Type 2) called SELECT, the benefits of semaglutide in lowering adverse cardiovascular events emerged early in the trial before significant weight loss had time to occur.” Vest, who was not involved in this study, leads a metabolic heart failure clinic at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, where she is the section head of heart failure and transplant cardiology and the George M. & Linda H. Kaufman Endowed Chair.

Study background and details:

This study’s findings are limited because results from animal models do not always apply exactly to humans. These promising findings need to be tested and confirmed in people before changes to patient care can be recommended.

Co-authors, their disclosures and funding sources are listed in the abstract.

Statements and conclusions of studies that are presented at the American Heart Association’s scientific meetings are solely those of the study authors and do not necessarily reflect the Association’s policy or position. The Association makes no representation or guarantee as to their accuracy or reliability. Abstracts presented at the Association’s scientific meetings are not peer-reviewed, rather, they are curated by independent review panels and are considered based on the potential to add to the diversity of scientific issues and views discussed at the meeting. The findings are considered preliminary until published as a full manuscript in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

https://newsroom.heart.org/news/low-dose-of-weight-loss-drug-may-improve-heart-failure-symptoms-with-minimal-weight-loss

View Original | AusPol.co Disclaimer