Who’s Immune To Conspiracy Theories?

There is just no way around the grassy knoll. The 1963 assassination of US President John F. Kennedy in Dallas near that now-infamous hill has given rise to thousands of variations on the same theme: Did Lee Harvey Oswald act alone or was there another shooter? Who else might have been involved? The list of possible co-conspirators seems endless-including the CIA, the mafia, the KGB, anti-Castro Cubans, or even Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson himself.

Conspiracy theories are certainly not a new phenomenon. In fact, some, such as the blood libel conspiracy theory against Jews, date back to at least the Middle Ages. Yet things started to change in the last decade or so, argues Scott Tyson, an associate professor of political science at the University of Rochester. This period saw an intense “weaponization of conspiracism among politicians” in the United States-on both sides of the aisle.

“I think now we’re just well past the point of no return,” says Tyson, who teaches an undergraduate class on conspiracy theories in American politics and whose research focuses on formal political theory, international relations, and the theoretical implications of empirical political models.

Three ingredients make up the so-called conspiracy ecosystem, explains Tyson:

A conspiracy theory, according to a warning by the European Commission (the executive body of the European Union), is usually without solid and publicly verifiable evidence. It typically centers on a person’s or group’s belief that events or situations are the result of a secret and often unlawful or harmful plot by powerful people or organizations.

Conspiracy theories thrive especially in environments where uncertainty, fear, or distrust are rampant, explains Tyson. Frequently people’s heightened level of wariness-of government, media, elites, or institutions-is the result of past public scandals (such as Watergate or the Tuskegee syphilis study), corruption, or a widespread sense of political disillusionment.

Conspiracy theories-Tyson prefers to refer to them as “conspiracisms” because they are devoid of rigorous scientifically tested theories-come in a wide variety. What unites them is usually a combination of four elements:

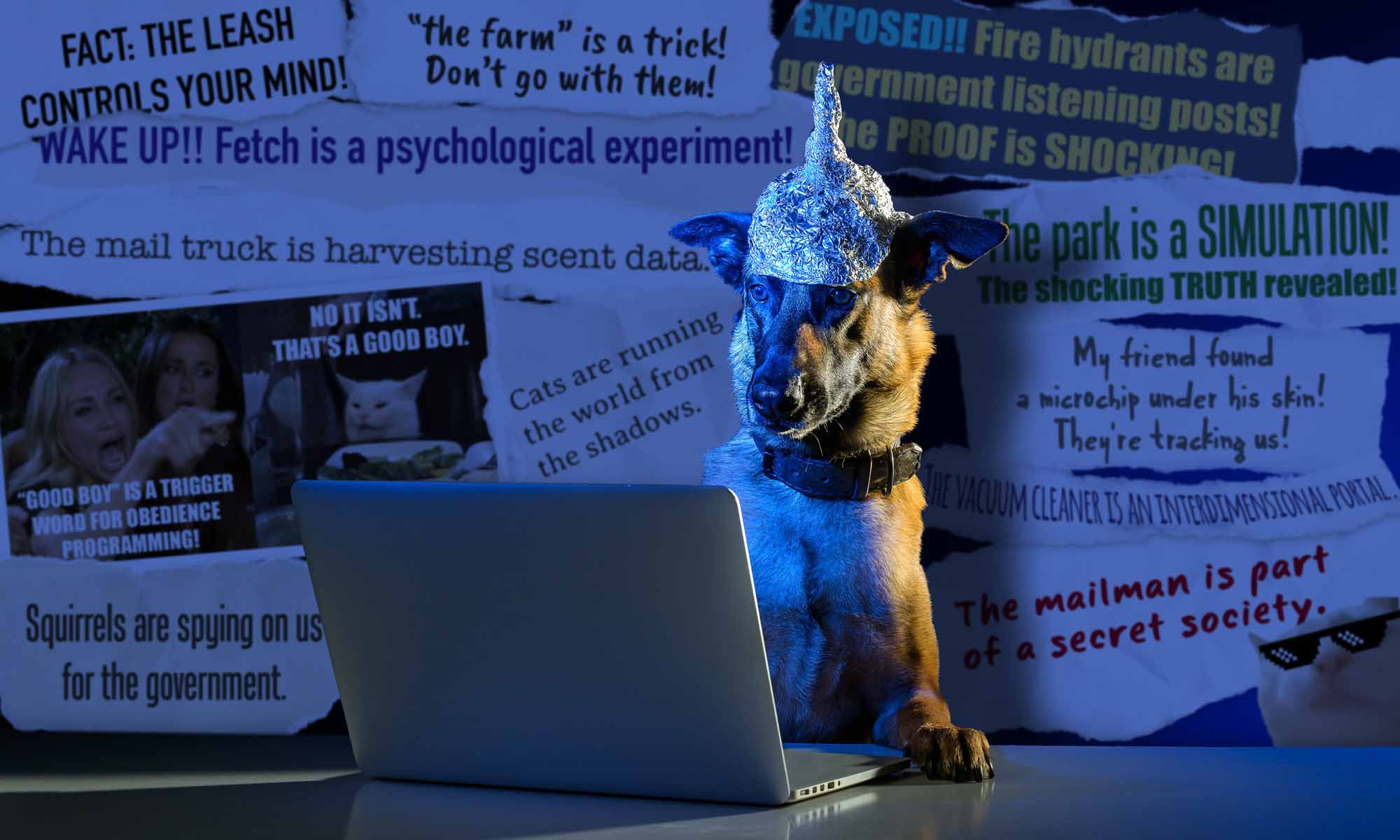

Many social media platforms have become echo chambers where almost anyone can easily find groups that validate one’s beliefs-even the most outlandish ones. Moreover, online algorithms prioritize content that is emotionally engaging, which means that sensational or conspiratorial content frequently gets pushed to the forefront. According to Tyson, people are more likely to believe these (false) tropes because they’ve heard variations of them many times before.

And while most conspiracy theories don’t lead to violence, they can and do when used as a mobilization tool and when endorsed by leaders, according to Tyson. “We’ve seen violence emerge from right-wing conspiracies because conspiracism has become fashionable on the right in the last 10 years,” says Tyson. “And political violence has become fashionable on both sides of the political spectrum in the last 15 years.”

By their very nature, conspiracy theories cater powerfully to basic human psychological needs. According to the self-determination theory of human motivation, developed by Rochester psychologists Richard Ryan and Ed Deci, these include the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Conspiracies exploit our fundamental desire to belong to a social group and feel connected to others. They often divide the world into “us” (the ones who know the truth) and “them” (the powerful elites who are hiding the truth). This division creates a sense of belonging and solidarity-that is, relatedness-with others who share similar beliefs.

Similarly, believing in conspiracy theories can help create a sense of autonomy, or a feeling of control over one’s actions and choices so that a person is no longer powerless in the face of unknown forces. Buying into conspiratorial thinking may also feel rewarding because it fosters a sense of moral or intellectual superiority for knowing the “real” truth.

Beyond appealing to these basic needs, conspiracism activates our innate cognitive biases-mental processes that can lead to illogical and irrational decisions by providing seductively simple answers and seemingly reassuring explanations for our complex and often chaotic world. One example is confirmation bias, in which people tend to favor information that supports their pre-existing beliefs. A conspiracy entrepreneur can exploit these natural tendencies to sow conspiratorial thinking in the audience. Furthermore, we are wired to detect patterns, even where none exist, a phenomenon referred to as illusory pattern perception. This skewed perception may make random events appear the result of deliberate, secret plots.

“All these biases are well-documented in the psychological literature, and it makes perfect sense that they’d be applicable to issues as important as the conspiracy theories of our time,” says Harry Reis, the Dean’s Professor and a professor in the Rochester Department of Psychology.

While fluctuating over time, the most widely believed ones in the United States are frequently government conspiracy theories, according to international data analytics firm YouGov.

Topping the list is the idea that JFK’s assassination was covered up-with 65 percent of Americans believing that more than one man shot the late president-according to a 2023 Gallup poll. Many Americans also buy into the notions that the terror attacks of 9/11 were an inside job, that the government continues to hide evidence of extraterrestrial life at Roswell, that secret elites control government policy behind the scenes, and that the NASA moon landing was faked in a Hollywood TV studio.

Interestingly, notes Tyson, most of the 9/11 conspiracies originated as left-wing conspiracies, moving from the left to the right political spectrum over the years.

Who believes in conspiracy theories? The truth is, hardly anybody is immune.

“We all are susceptible to falling into conspiracy black holes,” warns Tyson. It’s a myth, he says, that humans divide neatly into one of two categories-those who believe in conspiracy theories and those who don’t. Instead, most people are somewhat susceptible to believing in conspiracism, although some are more prone to being seduced than others.

“But I always tell students, ‘Don’t look at people who tell you a conspiracy theory and judge them because, in fact, we are all susceptible,'” says Tyson. “It could’ve been you.”

Scott Tyson

Associate Professor of Political Science

Tyson’s research focuses on formal political theory, political economy, conflict, authoritarian politics, external validity, and experimental design. He has authored or coauthored scholarly articles that have appeared in the Journal of Politics, American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, Political Science Research and Methods, and PS: Political Science and Politics.

https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/how-do-conspiracy-theories-work-explainer-653052/